Pennsylvania

New York

New Jersey

Delaware

Maryland

Virginia

Tom Roller- North Carolina

http://www.waterdogguideservice.com

After more than a decade of running his own charters off the southern coast of North Carolina, Capt. Tom Roller’s racked up a lot of fish tales.

Ironically, most “don’t revolve around fish.”

Roller, owner and founder of the Beaufort-based WaterDog Guide Service, explains it this way: “I spend a lot of time in a small boat with people. It’s a great way to get to know people really well.”

In return, they get to know the salty waters Roller grew up falling in love with. They get to understand why you can visit North Carolina and, instead of heading 60 miles off-shore toward the Gulf Stream, hunting out the big-game sport fish the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s southernmost state is largely known for, they learn about fishing near-shore, in-shore and along marshy flats.

While Roller never promises a big catch or perfect weather, most also walk away with incredible memories.

“Fishing has always been very important to me, and from a very early age, my father and grandfather impressed upon me that fishing was an avenue (to showcase) the importance of family, camaraderie, conservation and the love of the sport.”

A licensed U.S. Coast Guard captain, Roller rolled out WaterDog Guide Service after college in 2002. He offers fishing charters and tours throughout North Carolina’s Crystal Coast – from Beaufort and Morehead City to Atlantic Beach, Pine Knoll Shores and Emerald Isle.

Roller isn’t technically from the coast, having moved around a lot as a kid.

“We did spend a lot of time on the coast, though. My earliest memories are of the saltwater.”

When it came time to pick a place to start his own life, his own family, Roller made his way back to North Carolina, where, today, he lives within 200 yards of the water and spends every day on it.

“Being a full-time guide…is one of the best things that I can offer my clients. Not only am I on the water every single day learning and moving with the habits of the fish, but the success of my business is founded upon the happiness and satisfaction of my clients.”

His feature? Promoting and educating his clients on the fun and intensity you can have with light-tackle and fly-fishing.

“Fishing is not about who can go the fastest or who can sling the biggest fish on the dock – not every person wants to tug on a 300–pound sea monster. Some of us enjoy technique and style as much as anything. In protected waters and within sight of land, the miles of undeveloped barrier islands, winding tidal marshes and three local inlets, offer countless opportunities for fishermen to tangle with dozens of species.”

Asked if Roller has a favorite fish to hunt?

“My answer is always the same – whatever is biting,” Roller writes on his web site. “If it’s a fish, I enjoy trying to catch it, particularly if it requires employing new tactics.”

Roller’s equipment, and tactics, easily vary each trip – likely one of the reasons he can boast multiple citation catches.

“I have two different boats,” Roller said of his 23-foot Parker Deep Vee and a shallow-draft Jones Brothers Bateau. “Can’t really say what my key pieces of equipment are because I easily have 80 different rods. I could give you key pieces of equipment for every situation.”

And every client.

“I love bringing kids out on the boat. One of the greatest things about fishing is being able to pass the love of the sport on to a young one. My Dad started me fishing when I was 3-years-old and I never looked back.”

Roller has a good reputation for working with children, and an even better reputation for working with fathers. Roller has helped fathers throughout the years understand why fighting a good Blue Fish could make a stronger memory for a youngster than searching out that 300-pounder.

Blue Fish jump three feet in the air, Roller said. They pull on the line. And when you’re back at the dock, they are among Roller’s favorite fish to eat.

“Paul Greenberg, in his book Four Fish, comes to this conclusion – (Blue Fish) are a perfect recreational fish. They fight really hard. They jump. And they taste really good fresh. It encourages you not to keep very many of them.”

Greenberg may have written that passage specifically about Blue Fish, Roller said, but that philosophy is an admirable mantra to live by for all species.

Skip Feller- Virginia Beach, VA

Each summer in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Capt. Skip Feller watches as adults and children see the ocean for the first time, drop lines into the deep sea and near-shore waters, feel rolling waves and reel in salt-water fish.

“We take everything for granted working here, living here, growing up here. But these waters, they are a special place.”

Feller, who hails from of a well-known Virginia fishing family, is a third generation charter boat captain. Among other accomplishments, he set the 2008 world record for yellow edge grouper and in 1992 was named Charter Boat Captain of the Year. Today, he manages the fleet of head boats and captains that run out of Virginia Beach’s Rudee Inlet.

Feller earned his U.S. Coast Guard’s 100-ton captain’s license when he was 19.

“I never really pictured myself doing anything other than this. When I was in high school, I worked on charter boats. In the 90s, I branched out and bought a charter boat and ran out of Pirate’s Cove (in North Carolina). Came back in 95 to work with my father.”

Feller’s father “was one of the first people to have a boat in Rudee Inlet (Virginia Beach) back in the 70s. He bought the head boat in 1976…and basically started adding to the fleet.”

He sold the business in 2006. Today, Feller manages the legacy his father built – a legacy fleet of three fishing boats, like the 90-foot Rudee Angler licensed for 140 people, and three cruise boats, like the Rudee Flipper, used for dolphin and whale watching trips.

By the numbers, cruising the waters off the coast of Virginia is the most popular excursion Feller manages. Each summer, on the Rudee Rocket speedboat alone, Feller and his captains takes out more than 20,000 guests.

But fishing is no small business. Each year, Feller averages about 10,000 people on charter fishing trips that range from 16-hour day trips to 36-hour overnight adventures.

“The sea bass is a huge part of our fishery here. The fall, spring, winter - that’s what people come here to catch. September and October are our busy fishing months.”

While Feller prides the fleet on keeping up with the latest technologies on all the boats, especially the fish finding gear, the most important piece of equipment, by far, are the captains, Feller said.

“You have to have good people working for you who also take it very seriously,” Feller said. “It’s not just a job. You have to really live it so you can produce week in and week out.”

The fishing community may seem really large, but when it comes to word of mouth marketing, it’s actually quite small.

“If you have one bad trip, it’s amazing how fast the word gets out. These people, who are out for our 16-hour offshore trips, are paying $200 a person. That’s serious money.”

Unlike the guests he takes out fishing, Feller doesn’t always remember the fish he’s caught. Over the years, there’s easily been thousands. What he never forgets are the moments he stumbles upon a previously undiscovered sea wreck, marking a brand new fishing spot.

“With GPS being so precise these days, word gets out quickly on good fishing spots. So when you find a new spot, where nobody has fished, you remember those days…that feeling of finding that spot.”

Like his father, Feller has already passed on the family tradition of loving and working with people on the water. Wes Feller, Skip’s son, marks the fourth generation of Feller captains that’s runs charters out of Rudee Inlet.

“When he is in the wheel house, you could mistake him for an old salt with his talent on the water.”

Rick Etzell, Montauk, NY

There’s no doubt about it. Being a charter boat captain in Montauk, New York – dubbed the fishing capital of the Northeast, if not the world – is a competitive sport.

Not only do you go head to head with Mother Nature in hopes of bringing home an exciting catch, but you also compete with fellow captains for clients.

Years ago, all the “charter boats in Montauk were right here,” said Rick Etzel, nodding to a line of charter boats that includes his 43-foot Torres sport fisher, the Breakaway.

“Now, not only are there more boats, but they are all over the (Montauk) Harbor.”

Captains are also challenged by the reality of running a business that includes the hard costs of fuel, dock fees, maintenance and repairs and a boat.

“I learned early on from the old timers how to keep expenses down,” Etzel said. “Use the tide. Start up, work your way down. Watch your cruising speed. Do the work yourself. You aren’t just the captain. You’re a carpenter and electrician, a painter when you need to be, and an engineer.”

Despite the challenges many captains complain of, Etzel survives and day in and day out heads out on the water to face off with one of his greatest loves - “the thrill of the hunt.”

Etzel, a respected U.S. Coast Guard licensed captain in the recreational Montauk fishing community, is also the president of the Montauk Boatmen, Inc. where he works to help enhance the quality of the fisheries not just in Montauk, but also the entire state of New York.

He’s respected as a fisherman and for his history and love of his fishing community.

As a kid, Etzel called himself a “summer resident” of Montauk. His grandfather purchased a home at “The End” in 1945 where “I spent every summer.”

After graduating high school in another area of Long Island, Etzel moved to Montauk and worked in the fishing industry.

At 22, Etzel bought his first boat.

“Was going to fix it up and sell it. Before I knew it, I was married with children and running a charter boat business.”

Today, Etzel logs between 200 and 250 charter fishing trips each year. Half day trips run about $650, with full day trips ranging from $1050 to $1400, depending on how far off shore the fishing goes.

To make up income during slow periods, Etzel does a little commercial fishing with his rod and reel and sells his catch to wholesale fish dealers.

Somewhere in the mix, Etzel also does his volunteer work with Montauk Boatmen, Inc. The importance of getting involved in the legislative side of commercial and recreational fishing can’t be understated, Etzel said.

Like most fishing towns throughout the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s region, fishing in Montauk has an incredible economic multiplier effect.

“I take 1,500 people out on my boat each year. They stay in hotels. They eat in restaurants. They buy a t-shirt. That puts a lot of people to work. That makes fishing mean a lot more than catching fish.”

Jim Winn- New Jersey

Can’t get in touch with Jim Winn in New Jersey?

As soon as his voicemail message turns on, you know exactly why.

“Hey. It’s Jim. I’m probably out fishing.”

It’s true.

Winn, a volunteer with the Recreational Fishing Alliance of New Jersey and avid, lifelong fisherman, retired from a career in sales and now spends two to four days a week on the water.

If he’s not on the water himself, he’s probably with his grandson, who he taught to fish, or volunteering with the Alliance, because he’s determined to help protect the sport of recreational fishing.

“I know my father taught me how to fish, but it was so long ago, I can’t remember catching that first one. Fishing, it’s my drug of choice.”

Winn particularly enjoys saltwater fishing in his 14-foot “tin can aluminum boat. We fish hard (for a variety of in and off shore seasonal species). It’s not going out with a six pack of beer to sit back and relax.”

Many of the fish end up back in the water after Winn’s reeled them in.

“I keep what I eat and the rest goes back. It’s more about the sport.”

That’s why Winn calls his work with the Alliance so important.

“I go to boat shows, outdoor shows, fishing shows and try to convince people to join our organization. We’re lobbyists for recreational saltwater fishermen. You don’t even realize it, but fishing is so tangled up in politics, we need lobbyists for us, too.”

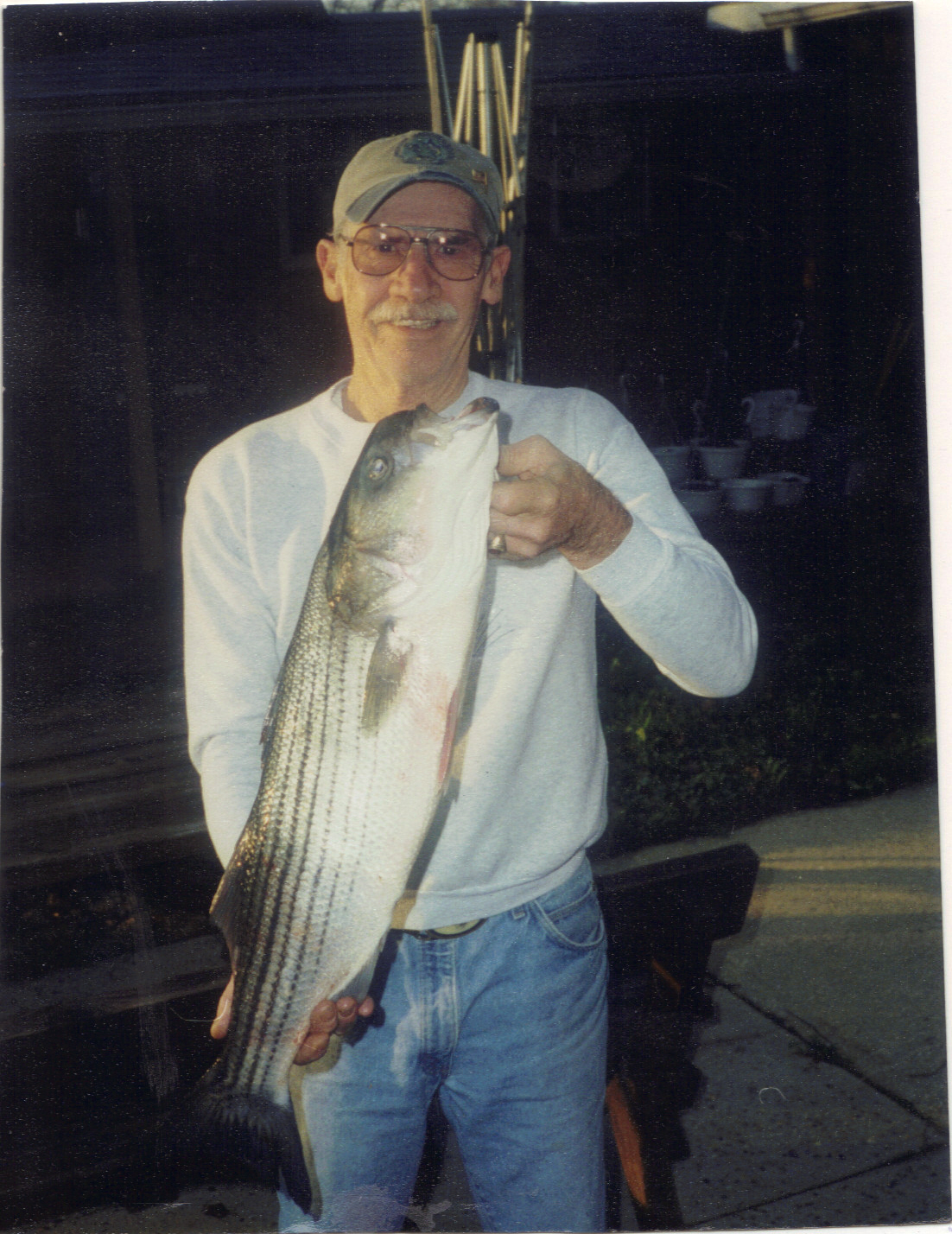

Frank Watkins- Ocean City, MD

It’s not that Frank Watkins believes that fishing has healing powers, or that reeling in a big sport fish off the coast of Ocean City, Maryland makes children with terminal illnesses forget about their own internal fight.

“But you get out on the boat and these kids, and their parents, get to think about something else for a little while,” Watkins said. “They get to make some memories.”

Watkins is a lifelong sports fisherman and the President of the Atlantic Coast Chapter of the Maryland Saltwater Sportfishing Association.

“I’ve been fishing since I could crawl,” Watkins said, of growing up on the New Jersey Coast. “I’m retired now and I get to fish a lot more for tuna and mahi offshore, flounder in the bays, black sea bass. Pretty much, if it’s going to bite, I’ll go fish for it.”

He also gets to work with children a lot more, teaching them how to fish, and volunteering with the association, where “we provide education and help improve the environmental habitat for fishing. It’s all so we have fishing – recreational fishing – available for our children and grandchildren.

“God’s blessed me,” said Watkins. “My kids, my grandkids, are all healthy and smart. I’ve had such a good life, and I enjoy fishing, that this is how I give back to the community.”

His favorite projects?

“We taught an entire sixth grade at a local school how to cast. Went out into the field next to the school building. Set up a couple of stations. It was amazing to see. We had almost 200 kids.”

For the adult fishermen, “we have guest speakers come to our meetings to show us how to, for example, handle flounder so they don’t get killed when bringing them to the boat. You have to minimize mortality of fish getting released, especially if your catch ones that are undersized.”

The association also works with local environmental groups to build mad made reefs off the coast of Maryland.

“We received a grant to build what looks like these giant jacks made of concrete. Off the shore here in Maryland, unlike North Jersey and New York, we don’t have structure, like rocks and boulders, to support habitat for black sea bass and a host of other species of fish. These reefs on the bottom create the nooks and crannies for marine life to get in.”

It may sound like a lot of work, Watkins said. But it’s important work.

“Fishing is important. It’s relaxing. Whether you’re on a boat or fishing from a stream, it’s a place you can go to get away from it all.”

Bill Baker- Lewes, DE

More than 5,000-square-feet of floor space. Fishing rods – about 2,500 of them – as far as the eye can see. Five hundred fishing reels.

Not to mention rigs and hooks, terminal tackle, a walk in freezer for bait, and “everything, just everything, that a fisherman could possibly want,” said Bill Baker, who founded Bill’s Sports Shop in Delaware in 1994.

Baker considers his shop among the largest, busiest and most well stocked tackle shop on the Delmarva Peninsula. It started out as just him and it’s grown into a family business where two of his five children now also work.

“My favorite sport is fishing,” said Baker, who’s been fishing his entire life. “I figured (after a career in beauty supply sales) this was a great way to enjoy my sport and run a business. I thought I was semi-retiring. As it turns out I’m busier now than ever before.”

The success of the store means Baker doesn’t have much time to fish himself, despite being a U.S. Coast Guard licensed captain and enjoying the hunt for black sea bass and flounder.

But it does provide the opportunity to share the love and excitement of bringing in the big catch with each of his customers.

“We get to hear all the good fish tales,” Baker said. “Fishermen bring in their fish and we take a picture, post it on our web site, Facebook, and print out a picture for them.”

For those who don’t bring in the big fish to document, Baker gets to hear about the good days on the water.

“Fishing…is the type of sport that the average person can go out and within a few minutes be enjoying time on the water – whether standing on the beach or on a boat. There’s a tremendous amount of fishermen who enjoy the sport just for the camaraderie of being with family and friends.”

As a bonus, he also gets to be part of the educational process for first time fishermen.

“I’ve got jetty, jockey, surf fishermen, off shore – just about every type of fishing available within just a few miles of the store,” Baker said. “We work very hard at making sure our customers are totally, totally familiar with the regulations so they don’t’ go out there and get a ticket doing something they are not aware of.”

His favorite fishermen to work with?

“I have a whole bunch of grandchildren and they all love to fish,” Baker said. “Other than the depletion of some of the fisheries and nature’s kill ratio, the big challenge for fishermen today is conservation. We need to make sure we can conserve enough to keep the fishery going for our grandchildren.”

Steve Bailey

Hatteras Village, NC- In the early 1980s, commercial fisherman Steve Bailey said he saw the writing on the wall.

Not only did he think regulations would make it harder and harder to make a living solely off the water, but he was also watching North Carolina’s small Hatteras Village transform from a small fishing town to “a tourist destination with oceanfront million dollar condos.”

So in 1984 he went into a risky business – literally.

Dressed in rubber fishing overalls, boots and a wet cigar hanging out of his mouth, Bailey pointed to a pile of flounder he caught that morning.

“Fish. Selling fish. It’s a risky business,” Bailey said of his retail fish market, which set up on Oden’s Dock in the heart of Hatteras Village and named Risky Business.

Unless you vacuum pack and freeze your fish – which Bailey will do for the charter fishing boat customers when they come in from their day trips – you have to sell fish within 24 hours.

In reality, Bailey’s Risky Business has been what helped him survive. He still gets to work the water, which he still enjoys, and is able to diversify his business model.

“We do a good business here,” Bailey said. “But there were some hard days. I remember when I bought a pig and a keg of beer the first time we grossed $1,000 in one day.”

On average, Bailey sells between 500 and 700 pounds of fresh seafood per week.

While most of Bailey’s customers are summer visitors, a few are local, year-round customers.

As Kerry Barnett, the store’s manager said, “most of the people who live here locally year round are fishermen themselves.”

Bailey’s seafood offerings range from tuna and mahi caught off of the North Carolina coast in the Gulf Stream, to North Carolina shrimp and crabs, to the flounder he and Barnett catch in their small Carolina Skiffs and scale, brine, fillet and sell.

“It really is a cool feeling to tell the customers that we really did catch this fish for you this morning,” Barnett said. “People appreciate knowing how fresh it is and that it went from the sea to their dinner plate so quickly.”

Russ Gibbons

Russ Gibbons

MJM Seafood Trading Company

Williamsburg, VA--Russ Gibbons’ customers might be surprised to know he doesn’t fish.

In fact, he says proudly when anyone asks, “I just don’t like it. It’s too much like work. If you see me with friends out on the boat and I’m holding a fishing rod, chances are I just dropped the sinker in the water without any bait to make it look like I was fishing.”

What Gibbons does love is life on the water and the sweet, savory taste of just about every species that comes out of it.

“I love a good seafood boil. Throw it all in a pot like a pack of Skittles and taste the rainbow.”

It’s why, in May 2011, following nearly three decades in the restaurant business, Gibbons opened MJM Seafood Trading Company in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Gibbons grew up in Virginia’s York County. His family hails from Maryland and Virginia’s shared Eastern Shore, both states in the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s region.

“I had the family that has oysters on the table for Thanksgiving. Seafood was a big part of my life. Clearly it still is.”

MJM Seafood Trading Company is a proud family business with one mission in mind, Gibbons said.

“Bring people the best, freshest seafood possible.”

For MJM, that’s being involved in the seafood distribution process from the start.

It means sometimes being on site when the fishermen arrive at the dock and unload fish onto a grading belt.

“Fresh, seasonal, products area always a higher quality. If I could walk out into a field and pick my own cow out for my steak instead of one already wrapped up at the grocery store, I’d do it.”

It’s trusting the dock masters he works with, and the regulatory enforcement system, to buy legal, fresh fish for pickup from the dock’s cold, storeroom. Gibbons pick ups, mostly whole fish, and delivers directly from the docks to kitchens in a large, white utility van.

Occasionally, Gibbons will process the whole fish he buys.

“I’m a business man. If I can make an extra $1 processing, I’ll do it.”

In general, he gets it to his customers as quickly as he can drive there. He has to.

“My marketing to my customers is your fish are less than 36 hours out of water.”

Plus, he doesn’t want to let his children down. His three children are very much a part of the business. MJM stands for the first letter of their names. Gibbons’ son designed the price sheet, one daughter’s voice is on the answering service and another daughter is “cute to ride around in the truck with.”

They are also his motivation.

Gibbons may not like to fish, but he does like to teach his children the importance of working hard for what you want in life.

“I may not have taught them to fish, but I have taught them the value of fishing and the relationship we have to nature.”

Eventually, he’ll teach them how to put together a seafood boil.

Ginger Nappi

Ginger Nappi, Martin Fish Company

Ocean City, Maryland- Ginger Nappi may have tried her hand at careers away from the water, but something always drew her back home.

“I wanted to be on the water. I wanted to be with the fish, with my family.”

Now she is. Nappi helps run her family’s Martin Fish Company in Ocean City, Maryland.

Martin Fish Company was founded by Nappi’s grandfather, then worked by Nappi’s father, and now by Nappi and other family members.

“I’ve been around fishing since I was born. In elementary school, (my brother and I) would take turns going out with dad on his day trips.”

Nappi’s father is Sam Martin, who now serves as the Vice President of Operations for Atlantic Capes in New Jersey.

“We’d get up at five in the morning…watch the sunrise on the deck while steaming out into the ocean. When the crew was hauling fish onto the deck, he’d hook me on to a cable and a life jacket so I could be on the deck and watch. We’d be up to our knees in fish.”

Once Nappi turned 18, she started helping out with the operations back at the harbor.

“Anywhere they need me, I jump in and help. Unloading the fish, packing them in boxes. I’ve been inside vats before, icing them up and packing them up. I’ve been slimy from head to toe.”

Martin Fish Company practically does it all at the harbor. The boats come in. We unload the fish. We pack it and either ship it out or sell it in our retail store.”

In the retail store, where Nappi spends most of her time, “we do whatever the customer wants. We sell whole fish, or process it. We fillet for restaurants, and steam crabs and shrimp.”

And, of course, there’s the secret family recipes.

“My grandmother came up with a bunch of soup recipes and clams casino. My aunt and I still make her recipes and sell them here.”

The selling feature for Martin Fish Company?

“It really is the freshest seafood possible. We get the fish right off the boats. There’s no middleman. It’s boat to market to customer.”

Will Nappi’s son head into the family business?

“It will be up to him. But I like knowing he’ll learn the value of working hard, that if you see something that has to get done, you jump in and do it. He’ll learn that here, even if he doesn’t become a fisherman.”

John Nolan

Montauk, NY - Shortly after 3 a.m., John Nolan walked down the pier of the Town Dock in Montauk, New York and toward the bright red hull of the fishing vessel he captains – the Sea Capture.

Despite his youthful face, and being one of the youngest captains in the small hamlet on Long Island, Nolan’s sweatshirt, ripped from years of fishing and dingy from days at sea, and five-o-clock morning shadow give him the look of a veteran fisherman.

Climbing on board in the dark, Nolan moved around, pulling ropes, flipping on switches and readying the vessel as if he’d been doing it since he was born.

In a way, he had. Nolan is the second-generation fisherman to captain his family’s tilefish boat. He watched his mother break the bottle of champagne over its bow when its construction was complete. He kicked fish on the deck and into the hole as a child. And when he was 8-years-old, he went offshore fishing with his dad for 10 days.

On this morning, Nolan headed out on another 10-day trip, 100 miles offshore.

“I did go off to college,” Nolan said. “That first year, I came home and did a fishing trip with Dad. I puked the whole time. I was miserable. But when I got home I got paid.”

Nolan came home from school, “never looked back,” and started working on the decks of the boat. He did that for more than two years. When fishing got tough, and the Sea Capture needed another captain, then 20-year-old Nolan got his shot.

“John paid his dues,” said big John Nolan, Nolan’s father. “It’s a requirement. We didn’t give him an inch. He really earned it.”

Nolan’s parents – John and Laurie Nolan – started the family tilefish business in the late 1970s and brought it to Montauk in 1980.

The Sea Capture may be one of three tilefish boats in Montauk, but they are responsible for roughly 25 percent of the tilefish caught in the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s region, which stretches from New York to North Carolina.

Fishing for the Nolans isn’t just what they do for a living, it’s a huge part of their family history.

Big John Nolan’s fishing started out before he met Laurie when he worked as a clam digger. When clamming got tough, he moved offshore to lobster.

“He sold lobster to my father,” Laurie said. “That’s how we met.”

Laurie worked the boats with John for years. When lobster fishing got tough, they tried their hand at tilefish. Eventually, they moved to Florida to bottom fish, which ended up being what set them up for successful tilefishing back in Montauk.

During their bottom fishing days in Florida, they used circle hooks on a long line. At one point, the gear for tilefish tactics transitioned from J hooks (pre-baited on the docks) to circle hooks (baited and snapped on the line while out at sea).

Since John and Laurie were already using that method, they were ahead of the game back in Montauk.

“They were really pioneers when they got here,” said another Montauk fisherman who’s known the Nolan family for decades.

The new style of fishing with the snap on circle hooks may have been more labor intensive, but it was better at catching fish.

So good, in fact, that, Laurie said, fishermen did real damage to the tilefish fishery, which was at one point declared overfished.

That’s when Laurie, now a veteran councilwoman with the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, got involved with the regulatory side of the business. She helped all the tilefish boats from Montauk through the process of developing a plan to rebuild the fishery.

Even as a regulated fishery, young John Nolan loves running the boat.

The Sea Capture is a four-man operation – the captain and three mates.

Their 10-days at sea are hard fishing days. Each starts 20 minutes before sunrise. Once there’s light, they start setting the line - miles and miles of baited hooks. They let the lines “sit” long enough to eat breakfast and then start pulling it in. Nolan steers the boat and takes hooks off the line at the same time. The other crewmembers gut the fish and get them packed into the ice-filled fish hole below deck. Each hook is re-baited as the fish come off.

There’s a morning and an afternoon set, Nolan said. The entire day is done about 3 a.m. and restarted just before the sun comes up.

“At sea,” he said, “you definitely sleep in shifts.”

Big John Nolan hasn’t been on the boat in a long time, and definitely not since Nolan started running it.

“I talk like I miss it,” big John said, smiling. “But if someone really asked me to go out, I’m not sure that I would.”

Big John does stay very involved with the boat at the dock, though, helping with maintenance and long term planning. Laurie still stays involved, too. Both Johns will tell you she runs the whole show, talking to the markets, managing the books and keeping them all straight.

As dangerous and hard as life at sea can be, Laurie said, she doesn’t worry about Nolan while he’s fishing.

“It’s when he’s on land in the middle of July and I hear sirens that I worry,” she said. “He knows what he’s doing out there on the water.”

Sam Martin

Vice President of Operations of Atlantic Capes Fisheries

Sam Martin isn’t just a fourth generation fisherman. He’s a fourth generation fisherman who’s been involved in every aspect of the fishing industry, from watching his father work boats to becoming an executive with one of North America’s largest fleet operators.

Martin, now the Vice President of Operations of the Cape May, New Jersey-based Atlantic Capes Fisheries, Inc., is from Ocean City, Maryland where his family started Martin Fish Company.

“I fished my entire life, grew up through the ranks,” Martin said. “I have a high school education, but I never went to my high school graduation. I went fishing instead.”

Leading the operations for Atlantic Capes means managing the 20 boats in the fleet.

“The experience I have on vessels helps me understand what the captains go through on the ocean. I’ve been there. I understand what the guys need in the oceans to fish safely and efficiently, and to evaluate the fleet to know what we need today and in the future.”

Atlantic Capes is largely known as a leading harvester and marketer of scallops – they are responsible for about 25 percent of the East Coast scallops – but also sells flounder, scup, clams and squid.

With all of Atlantic Capes’ divisions – including operations like clam processing and aquaculture farms – they employ more than 200 people.

“We really work hard trying to grow jobs,” Martin said. “It’s about creating partnerships and seeing who we can keep in business rather than get out of business. Creating partnerships creates strength. That creates community, which is incredibly important in fishing.”

Last year alone, Atlantic Capes sold more than 14 million pounds of scallops, and that’s a combined figure from those harvested by Atlantic Capes-owned boats and boats they’ve created those partnerships with.

“We have a very strong company,” Martin said. “It’s a very strong business model.”

Its success is largely based on its vertically integrated system.

“Basically that means we get it all the way to the plate,” Martin said. “We don’t sell directly to retail, but we do sell to companies – like Costco. We process and package it to our customers’ specs. A company gives us their label and we put it in their bags and cold store it.”

Martin proudly states that his family now has fifth generation fishermen working the fish from Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s regulated waters. His daughter, Ginger Nappi, helps run the still vibrant Martin Fish Company in Ocean City, Maryland.

As for Martin, “occasionally I miss being out on the water, that is, until the wind blows real hard. At the same time, I get a lot of joy assisting captains and the crews out on the ocean. Makes me happy to coordinate a fleet like this.”

Robbie Scarborough

There are plenty of challenges out there for commercial fishermen today, said Robbie Scarborough, who’s spent his career on the waters off the coast of Hatteras Village, North Carolina.

There’s changing regulations, dangerous weather, keeping up on updated technology, and following schools of fish as they move along the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s coast.

But at the end of the day, commercial fishermen are businessmen, Scarborough explained, as he packed out a “fair day’s catch,” or about 500 pounds, of bluefish and butterfish at Avon Seafood Company in Hatteras Village.

“Our biggest challenge is trying not to flood the market,” Scarborough said.

It’s the proverbial catch-22. When the fish are running, “you catch them because if you don’t the guy in the boat next to you will. Besides, you don’t know if they will be back tomorrow. But then if you have too many fish at market, they lose their value.”

One fish species, Scarborough said, “could bring you $2 today and 90 cents tomorrow.”

After more than 30 years of fishing, though, you learn how to balance it.

Scarborough is a blue blood, born and raised, Hatteras Village fisherman.

“Fishing isn’t just important to Hatteras, it’s the blood of Hatteras.”

It’s what Scarborough’s father did and what he figured he eventually would do. He didn’t know for sure until he was 15 and “was out on the boat and didn’t get sea sick anymore. Figured that meant I should be a fisherman.”

Twenty years ago, he bought his first commercial fishing vessel and named her Shear Water.

Fishing isn’t a job, Scarborough points out.

“A job is something you do nine to five and hate going to it,” he said. “This isn’t a job, it’s a labor of passion. You’re not going to get rich doing it, but you’ll get to be on the water and will always have a good dinner.”

Scarborough will hook and line fish for some species, but largely, Shear Water is outfitted with gill nets.

Keeping up on regulations, being a fisherman in a border area between two federal agencies, isn’t too hard, he said, “if you have a good wife at home,” Scarborough said. “I can read, write and sing, but my focus is fishing. She keeps me regulated.”

Ask Scarborough if he fishes for fun, and you get a huge smile and hearty laugh.

“Fish for fun? Fishing for fun cost me my first two wives. My wife now likes me better when I fish for fun.”

Paul Farnham

Montauk, NY

Fishermen are today’s undervalued heroes.

Paul Farnham passionately believes that.

As hunter-gatherers, fishermen are among the “last of the indigenous people in today’s world – a fast, paced technology driven world. Those guys on the back of the boat, they are my heroes. Real true heroes. They go out in brutal weather. They don’t get paid a lot. They still do it.”

And that’s why Farnham spends day in and day out welcoming commercial fishing boats back to the Town Dock in Montauk, New York, practically the northernmost port in the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s region.

Farnham doesn’t own the dock. He’s not even a wholesale fish dealer. What Farnham offers fishermen in Montauk, through his company the Montauk Fish Dock, is unique, he said.

Simply put, “we unload and freight forward.”

Commercial fishing boats pull up to Farnham, whose team helps unload the boat (called packing out), weigh, ice down and package. Then he ships it.

Most docks have wholesale operations right there, he said. Fishermen unload and sell their catch in one place.

“Our service provides the opportunity for fishermen to unload and sell and market themselves to whoever they want,” Farnham said.

Most of the fish are sold on consignment to Fulton Fish Market in nearby New York City, but some of Farnham’s clients ship their fish overseas, as far away as the West Coast and to various wholesalers outside of the area.

Farnham, originally from Canada, worked in and around commercial fishing all of his life. He bought his unpacking and freight forwarding business in Montauk in 1988 and has been a staple on the docks ever since.

So much so that in 2006, while battling cancer, Farnham never missed a day of work. He would get his chemotherapy treatments and return to the dock.

Ask Farnham to describe himself and he’ll tell you “I’m first a cancer survivor. Then I’m a fisherman. You really have to be a survivor to be a fisherman these days.”

Many fishermen, when asked about the challenges to their community today, talk up regulations.

“Regulations are a given. Our challenges are our survival. We need docks to unload. Our threats are real estate, environmentalists and the government.”

Farnham leases his unloading property at the dock. Within throwing distance is a piece of property, he said, sold eight or nine years ago for just more than $1 million. Today it’s valued at more than $4 million.

Then there’s the constant work to ensure the market isn’t oversaturated with fish, yet properly priced for the consumers to eat and fishermen to still make money.

“By the time fish gets to someone’s plate, there’s a lot of hands that have touched it. A lot of middle men.”

From the fisherman to Farnham, Farnham to the delivery driver, from the wholesaler to the restaurant, and finally to a kitchen and a plate.

Each time, a few more cents of operating and handling fees add on. On average, for example, Farnham charges 18 cents per pound of fish unloaded, iced and shipped.

Looking toward the future, Farnham plans to get involved in reducing “the number of hands each fish goes through” and open something of an online fish market.

“I’d like to be able to unload the fish from here and ship it directly to the consumer. This way, the consumer saves money and gets real deal, same day, fresh fish” from his fishermen heroes.